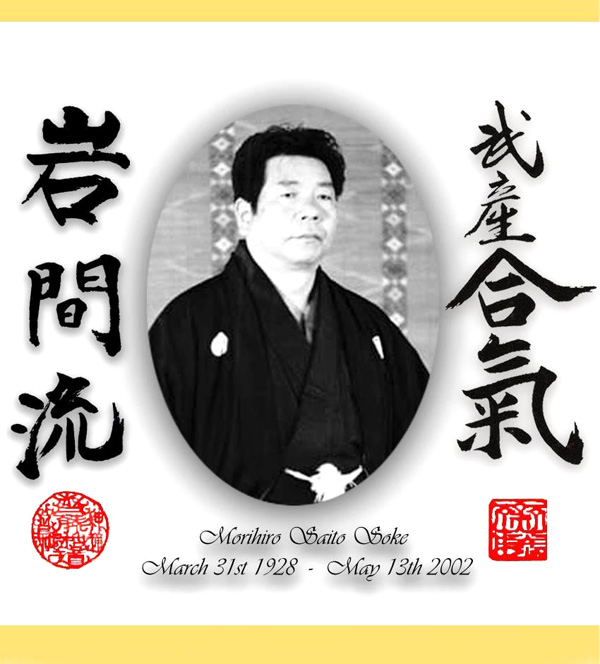

Today marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of our Master Saito sensei. RIP sensei sadly missed

きょうは斎藤先生死去20周年 Kyō wa Saitō sensei shikyo 20-shūnen

本日は、斉藤先生がお亡くなりになって、20回忌です。 どうか安らかにお眠りください。私は先生に永遠に感謝申し上げます。

Honjits wa Saito sensei ga onakunarini natte nijukkaiki desu. Doka yasurakani onemuri kudasai. Watashi wa sensei ni eien ni kansha moshiagemasu.

Iwama Style

As far as I know the phrase Iwama Style, did not exist while Kaiso ( O-sensei) , the founder, Morihei Sensei was alive.

How come this phrase is now widespread among Aikido people all over the world? There is no doubt that it naturally began to be used by a lot of uchideshis who visited Iwama. They are people who were inspired by keikos in Iwama, whose atmosphere was completely different from what they had experienced until then.

In Kaiso’s lifetime, the Japanese were living through turbulent times. Shortly after World War II ended, Morihiro, my father, became a pupil of Kaiso, and was training with Tohei Sensei, who had returned from the war and went to Iwama from his home in Tochigi prefecture.

At that moment, Iwama was little-known and there was no uchideshi from overseas. My father started to accept uchi deshi little by little, and to go abroad in order to hold seminars.

For other students of Kaiso, they were desperate to eat after the war. Even though they were called by Kaiso, they had to give priority to cultivate their fields in order not to starve to death. Eventually they came to join keiko less and less often.

My father and mother kept serving Kaiso and his wife to the point where they would faint due to illnesses. In the meantime, many people came to Iwama and offered to help them. Nobody could, however, stay for several days or even for one or two days, which shows that it was not that easy to work under Kaiso.

For my father, he was lucky to be able to train alone with Kaiso. He must have been so happy to train weapon techniques in between helping Kaiso in the fields that He would feel like his fatigue from the field was taken away.

When Kaiso visited a Judo dojo in Nagoya, he said to the teacher of that dojo, “ You should come to Iwama after I die. ” After Kaiso passed away, that teacher invited my father to teach in his dojo. At the party after keiko, that teacher said, “Today I understood the meaning of Kaiso’s words which he gave me when he was alive.” My father didn’t know that Kaiso left such words until he was informed by that Judo teacher, and tears didn’t stop streaming down from his eyes. My father often told me about this story.

I’m so proud of my father, who had continuously served Kaiso for 24 years since he was 19 years old, and mother as well. They dedicated their whole life to Kaiso protecting his spirit and technique, Aiki Shrine and Ibaraki Dojo. I want to meet them with a smile in the afterlife. I will not be able to show my face to Kaiso or my parents unless I leave something to honor the life and work of my great father, Morihiro Shihan.

Hitohira Saito Headmaster of Iwama Shinshin Aiki Shurenkai

岩間神信合気修練会長 齊藤 仁平

A Tribute of T.K. Chiba sensei to Morihiro Saito sensei.

The world of Aikido is once again bereaved by an immense loss, that of Morihiro Saito Shihan who died on May 13, 2002. For many years, he had followed the teaching of the founder, Morihei Ueshiba, and was one of his most senior students. He had become the guardian of the Aikido Temple in Iwama (Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan). One way or another, Saito Sensei's great influence is still exerted on almost every continent.

He often called his art "traditional Aikido" and there is indeed no doubt that in it – in its very essence as well as from a historical point of view – the mark of a direct transmission of the founder's teaching was present. I was lucky enough to be able to follow Saito Sensei's teaching when I entered the Iwama dojo as a ushideshi in the late 50s and also when he came to the Hombu Dojo one Sunday a month in the early 60s. It still seems to me to hear the sound of his footsteps when he left his house at dawn to do the fifty meters that separated him from the dojo of Iwama where he was going to give his first class of the day. While the very particular sound of the geta (wooden shoes) resonated through the frozen pines I had to wake up, thinking "here it is coming". I had to be ready, not only for the training on the mat but also to be sure that everything had been done correctly. Not a single thing, no matter how small, should have been omitted or forgotten, not even once. Saito Sensei provided the first morning classes as well as the evening classes in Iwama whenever he was not rotating at the National Railways.

O-Sensei also sometimes taught in the evening or just came to observe. He sat in front of the kamisa without a word, motionless, with an eagle's gaze, while Saito Sensei gave the class. He often emphasized the notion of katai-keiko, which can be translated as "solidly" but really means with energy, vigorously, with all his strength, without saving his power, without playing.

The training and atmosphere in Iwama were not only different from what I experienced at the Hombu Dojo but in all respects opposite. At the Hombu Dojo the emphasis was on the flow of ki so that at first I was totally lost. Most of the practitioners in Iwama were local farmers, people who worked hard in the fields all day. Their bones were thick and their physical strength was great. They possessed a typical trait of the region called "Mito kishitsu", a kind of manly character comparable to bravery. It was actually a very different culture than the one found at the Hombu Dojo in Tokyo. Living in the capital, Hombu practitioners were either office workers, intellectuals, businessmen, or politicians and students. Hombu practitioners who ventured to Iwama must have looked pale and weak city dwellers compared to the country people who trained there. And it is true that the practitioners of Iwama treated us like students of the Hombu Dojo and as such challenged us and led us the hard life. It was a matter of survival for the members of the Hombu, even for the ushideschis of which I was a part. And at the top of this mountain that we had to climb with all our strength was Saito Sensei. Of course Iwama was not very popular in the eyes of the ushideschis of the Hombu Dojo, not only because of the challenges they faced but also because their daily obligations as uchideshis of Iwama were very painful: work on the fields, cleaning the Dojo and the temple... Worse still, we had to take care of the old couple: O-Sensei and his wife. Most of the young people of the city could not bear this, accustomed as they were to the hectic life and luxury of city life. From time to time, during the day, O-Sensei gave classes in the woods, outside the Dojo. Most of the time, a very intensive work of yokogi-uchi alone or with a partner constituted the essence of the course. This is a well-known traditional training method at the Jigen School in Kagoshima, southern Japan, which involves performing continuous strikes on bundles made of freshly cut branches arranged on a structure of wooden braces. During my first participation in this training, I lost the skin of my hands and began to bleed for ten minutes.

Saito Sensei always seemed to feel O-Sensei's presence whether he was physically present in Iwama or not and his teaching always had the same content: the basics, katai-keiko. I especially remember a demonstration he performed with other high-level shihans in front of O-Sensei during the New Year celebration at the Hombu Dojo. He demonstrated katate dori from ikkyo to yonkyo just as he did in his classes. He knew how reckless it was to demonstrate anything else in front of O-Sensei.

I am well aware of Saito Sensei's service to the world of Aikido and his immense contribution. As far as I'm concerned, not only do I think he was one of the greatest Aikido teachers, but he was also very devoted to O-Sensei and his wife in the last years of their lives. Obviously, this is proof of a deep respect and unwavering loyalty to his teacher. I often wonder if I myself would have shown so much mental strength to achieve such a degree of self-sacrifice and perform such a large amount of work, a task that even members of O-Sensei's own family would have hesitated to accomplish!

When one knows the character of O-Sensei and his wife, one can easily imagine that the task was not simple. They had very different values than the Japanese of today. When I look back on it now, I wonder if there was something much stronger than just respect and fidelity when it came to the relationship between Saito Sensei and his teacher. I imagine that Saito Sensei had been introduced to a kind of art of living that he would have buried deep in his heart and taken with him in death. For me this is the perfect classical model, embodied, of the very essence of the art of the warrior.

As generations follow one another, this part of Saito Sensei's life tends to fade from memory or disappear in favor of the official history of Aikido as presented by the official authority. This very private aspect of Aikido history – the dedication shown by Saito Sensei in putting himself and his family at the service of O-Sensei – deserves to be viewed with respect and gratitude and must be passed down from generation to generation. I think it is my responsibility to write these few words, as a direct witness to part of this story.

Thus ends the little elegy that I wanted to offer in honor of Saito Sensei. I pray with all my heart that he will rest in peace forever.

Gassho

Palm to Palm,

T.K. Chiba

San Diego, California

May 16, 2002.